Why Didn t Cottage Industry Continue in Britain

Cotton, a valuable raw material and a mainstay of the textile industry, has been around for centuries and remains one of the most crucial resources to this day. Cotton has been used by humans as far back as the most ancient civilisations but for Europeans, it was not until the age of exploration and maritime trade that the material became highly sought after.

Back in 4500BC the ancient civilisations of South America were cultivating cotton. In Mexico, archaeological digs have uncovered fragments dating back centuries, showing the common use of fabrics with cotton accessible from the coastline where conditions were most humid. When the Aztecs conquered the areas of cotton cultivation it became a luxury product, giving status for those that wore it and forming part of Mesoamerican culture.

Hundreds of years later on the continent of Europe, imperial ambitions were growing, instigating vast explorations and journeys into the unknown. For the Spanish, led by the Conquistadors, the discovery of South America resulted in unearthing cotton as a raw material for clothing. Initially, this made little impact on the invaders who favoured clothes produced in other materials, forcing the Mexicans to adapt. By 1580, wool and silk had been produced extensively. Moreover, the commercialisation of cotton proved difficult and it would not be until the seventeenth century that it was truly embraced as a raw material for the textiles industry to export.

Meanwhile, British imperial ambitions led to the creation of the East India Company, a joint-stock company which allowed maritime trade in the region of the Indian Ocean and beyond. The company became responsible for around half of the world's trade in basic commodities including silk, spices, tea, opium and of course cotton. When the raw material of cotton was introduced to Britain the demand grew and its value soared alongside its production.

It was first imported to Britain in the sixteenth century, composed of a mixture of linen or yarn. By 1750, cotton cloths were being produced and the imports of raw cotton from areas such as the West Indies continued to grow. The impact of Britain's imperial trade links allowed cotton as a fabric to have a dominant impact on culture, clothing and style. By the eighteenth century, the middle classes were seeking a fabric which would meet their demands for durability but also colour and ease of washing; cotton fitted the bill.

It was during this surge in popularity that the East India Company continued to increase its imports of calico, a cheap cotton fabric from India. This met the growing demands from the poorest in Britain and found itself on the mass market. This subsequently had a negative impact back in Britain for the local manufacturers, so much so that in 1721 the Calico Act was passed by Parliament, enforcing a complete ban on calicoes in clothing or for domestic use. Two decades later the ban was lifted; the industrial revolution had sparked a wave of engineering phenomenon and inventions, allowing Britain to compete on the world textile market.

New inventions would revolutionise the textile industry, aid manufacturing and have a huge cultural and social impact on the lives of people in Britain. The spinning jenny invented by James Hargreaves and the water frame created by Richard Arkwright made it possible for large scale production. The engineering feats of the day were revolutionary and for the British Midlands, manufacturing became the backbone of the area. By the late 1700's cotton products would account for around 16% of Britain's exports; a few years later in the early 1800's this would multiply to around 42%. Britain was dominating the world market.

The raw material proved increasingly useful in its dexterity and versatility as a product. New ways of producing and combining the commodity allowed for the creation of velvet. This would be easier to produce than silk as it was much cheaper and also could be printed much easier than wool. The use of cotton therefore dominated fashions and styles of the day with more and more people gaining access to this once ancient precious commodity.

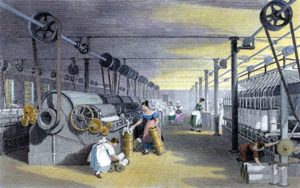

Manchester, 1840

Manchester, 1840

The value of cotton for the British Empire was enormous and in order to maintain the edge on their competitors, the country invested in technology that would save time and allow for a massive scale of production. Furthermore, to prevent competition from the likes of India, Britain imposed protectionist measures in order to restrict imports whilst also forcing the Indian market open to British goods. The colonial rule of India helped to cement Britain's monopoly over the cotton producing market, contributing to the continually growing commercial success of the Empire.

In Britain, the cotton industry was based in the Midlands, particularly Nottingham but also further north in Manchester, nicknamed 'Cottonopolis'. In the late 1700's the concentration of production and manufacturing took place in Lancashire, with mills popping up in Oldham and Bolton. The local population became dependent on the local mills for work and much of northern society was shaped around growing industrial production.

Carding, drawing and roving to produce cotton thread in a Lancashire mill, circa 1835

Carding, drawing and roving to produce cotton thread in a Lancashire mill, circa 1835

The impact of working in factories was a harsh and dangerous reality for many. Whilst the industrial revolution had positive effects on the economy of Great Britain, socially it created many more issues and new laws needed to be passed in order to protect workers' rights. Children as well as adults were enduring tough conditions with long working hours and in 1839 around 200,000 children were working in Manchester mills. The likes of Karl Marx sought to visit the area in order to observe the harsh conditions and poor provisions for workers, perhaps influencing his text 'Das Capital'.

The burgeoning cotton industry based in the north west of England had made Britain the 'workshop of the world' but at a great social cost. Nevertheless, Britain was gaining global prominence for its trade, production and new innovative manufacturing techniques. The industry was accounting for around 5% of the national income with hundreds of thousands of people employed as spinners or weavers.

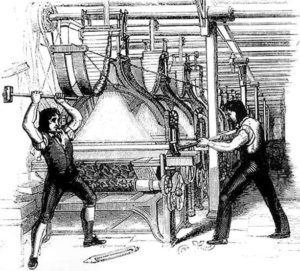

The fast paced change which took place during the industrial revolution did also have a negative effect on those who became dependent on the trade. In 1779 a group of textile workers based in Manchester known as 'Luddites' rebelled by destroying and raiding the factories which were putting them out of business. The introduction of new machinery rivalled their handmade skills, forcing many into difficult situations. The cotton industry had become the main source of employment for many: the advent of new technology threatened their livelihood. These issues would be a continued source of discontent for those being replaced by machines and left behind in the pursuit of profit.

The upward trend of growth for the cotton industry eventually reached its peak just before the First World War. The exportation of cotton ceased and contributed to the gradual decline of Britain as a leading manufacturer. After this time, despite a brief peak in the Second World War, the twentieth century witnessed the continual breakdown of the industrial heartlands of Britain. By the 1980's mills were being closed as often as once a week.

Countries such as Japan had begun to set up their own factories and were now producing material with much lower costs. In 1933 Japan became one of the largest cotton manufacturers, leaving the northern powerhouses of British industry behind. For the Lancashire mill workers, lives would never be the same. Today, abandoned mills, factories and industrial sites are all that remain of the industrial revolution which once upon a time torpedoed Britain into economic triumph.

Cotton had such a profound impact on Britain, changing its fortunes and facilitating innovation and new ideas. It became the centrepiece of the developing industrial revolution which impacted the country socially, economically and culturally for generations. Who knew a fabric which we all take for granted could have such a big impact?

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Source: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Cotton-Industry/

0 Response to "Why Didn t Cottage Industry Continue in Britain"

Post a Comment